Last week I was kindly asked to speak at the Amsterdam Investor Forum about innovation in a world of uncertainty and complexity.

I'd spoken at the event 7 years before, so it was a good opportunity to reflect on what had changed in the world over that time period (in summary: a lot).

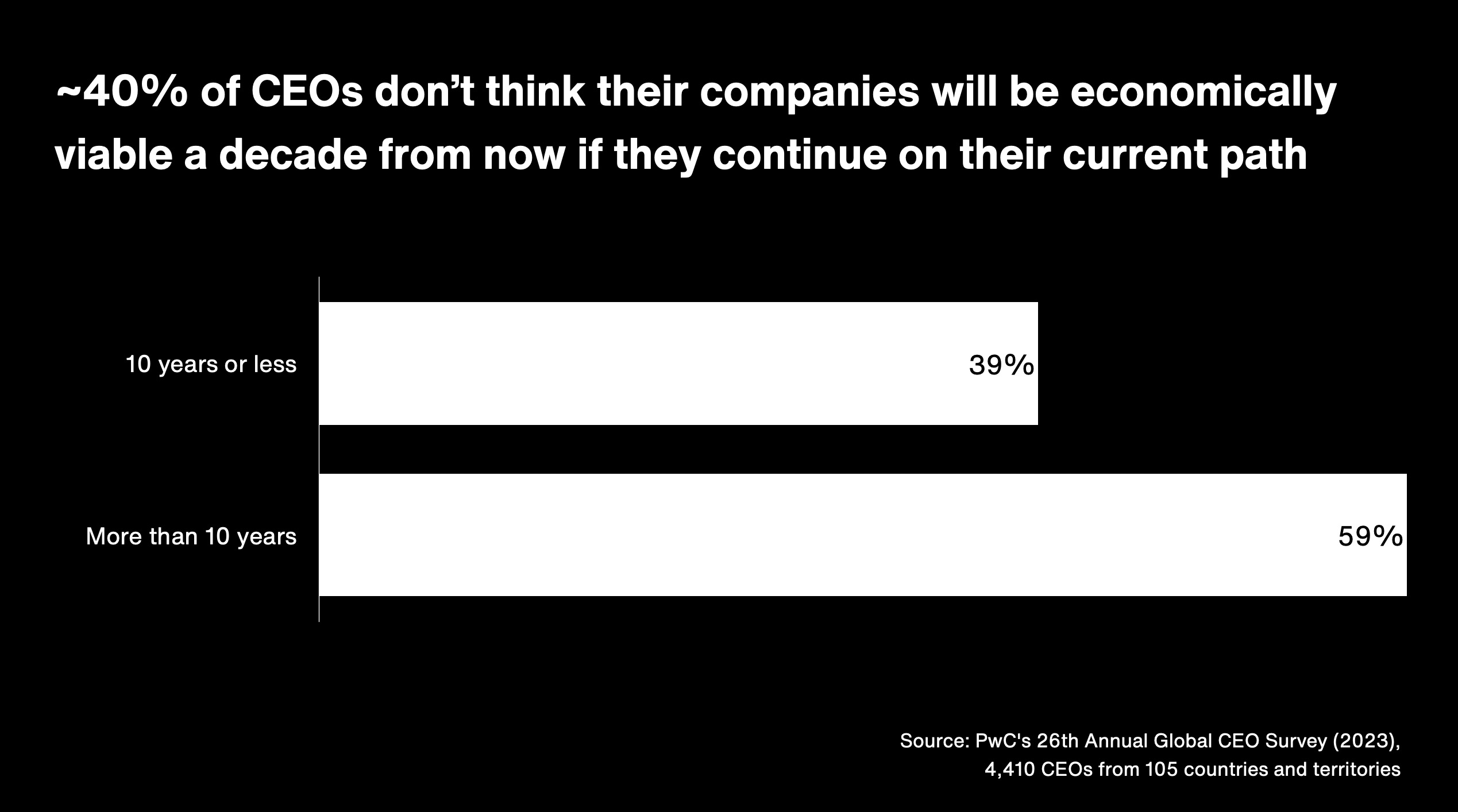

Apparently the second best way to start a speech is a surprising statistic, so I dug around the latest consultancy reports to find something interesting. A stat from PwC's Annual Global CEO Survey seemed to fit the bill:

This fact, contrasted with Mckinsey's anecdotal evidence that 94% of executives are dissatisfied with their innovation performance, summarised the conflict that I've observed working with large organisations over the last decade.

Everyone - at every level - recognises that a seismic shift is needed in the way that we work, live, sell, buy and consume. Yet the inertia is so great, so heavy, so overwhelming, that it's almost impossible to make any progress.

Whether it's the world's insatiable thirst for oil despite a climate crisis, or the fact that in 2022 the average employee experienced 10 planned enterprise changes, real innovation and change is hard to achieve.

I was once sitting in a CEO's office - a beautiful, mahogany lined room with all the trappings of power. I asked him why he thought innovation was so difficult in the business.

"Well, it's simple, no one reads my emails"

How could this be possible? The CEO was the most powerful person in the organisation, and yet they were unable to get their message across.

Time and time again, I've seen this pattern repeated. Diktats regarding change and innovation are issued from the top; labs are opened; consultants hired - and then the labs are closed, the consultants fired, and the diktats forgotten.

Why is change so hard?

Over the last seven years there as been a huge amount of innovation in the world. Whether it's AI, blockchain, IoT, 5G, VR, AR, or any of the other buzzwords, the technological world has changed dramatically. But counter-intuitively - from what I've observed - this makes systemic change harder to achieve.

I think there are three key reasons for this:

External technologies turn your (costly) competitive advantage into a commodity

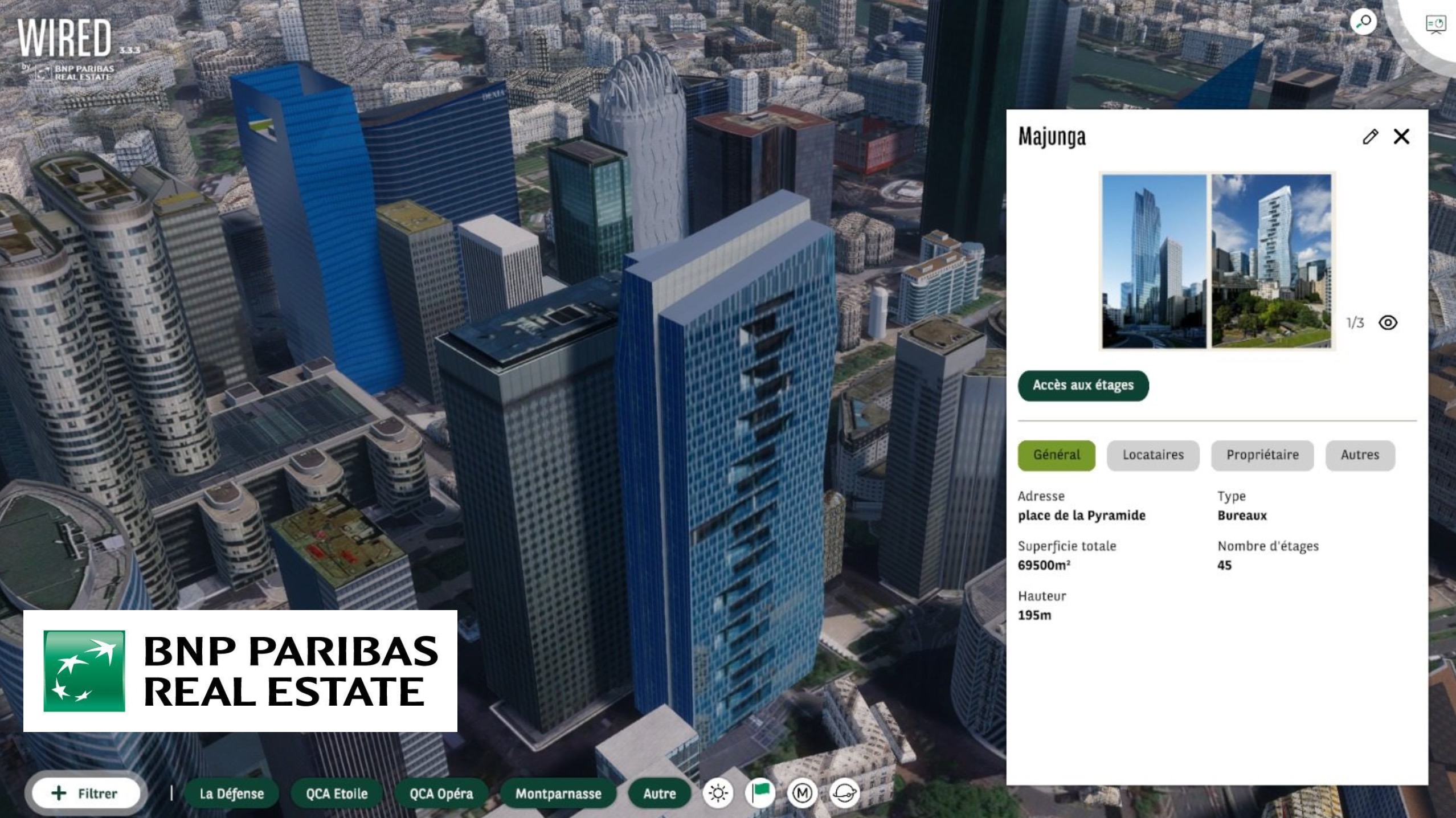

Wired, the first immersive real estate data analysis tool by BNP Paribas launched in 2021. The platform allows an investor in Hong Kong to visualise a building they're planning to buy in Paris, and see the impact of different scenarios on the value of the building.

With this tool there's a nice problem/solution fit, the persona is clearly defined and the technology works well. I don't know how much it cost to build, but I'd guess it was a lot. 3D modelling of all the relevant buildings in Paris, and the ability to visualise them in VR is not a cheap exercise.

Then, in 2023, WorldBLD launched a platform that allows you to procedurally generate 3D models of any building in the world, and visualise them in VR.

Not only does this instantly make Wired look obsolete, it also means that the cost of building a similar tool is now a fraction of what it was before.

What was your (costly) competitive advantage is now a commodity.

External technologies consume all the innovation oxygen

"[INSERT NEW TECHNOLOGY HERE] is changing everything" cries the [INSERT MEDIA OUTLET]'s front page.

Blockchain is changing everything, AI is totally changing everything and the metaverse is about to change everything.

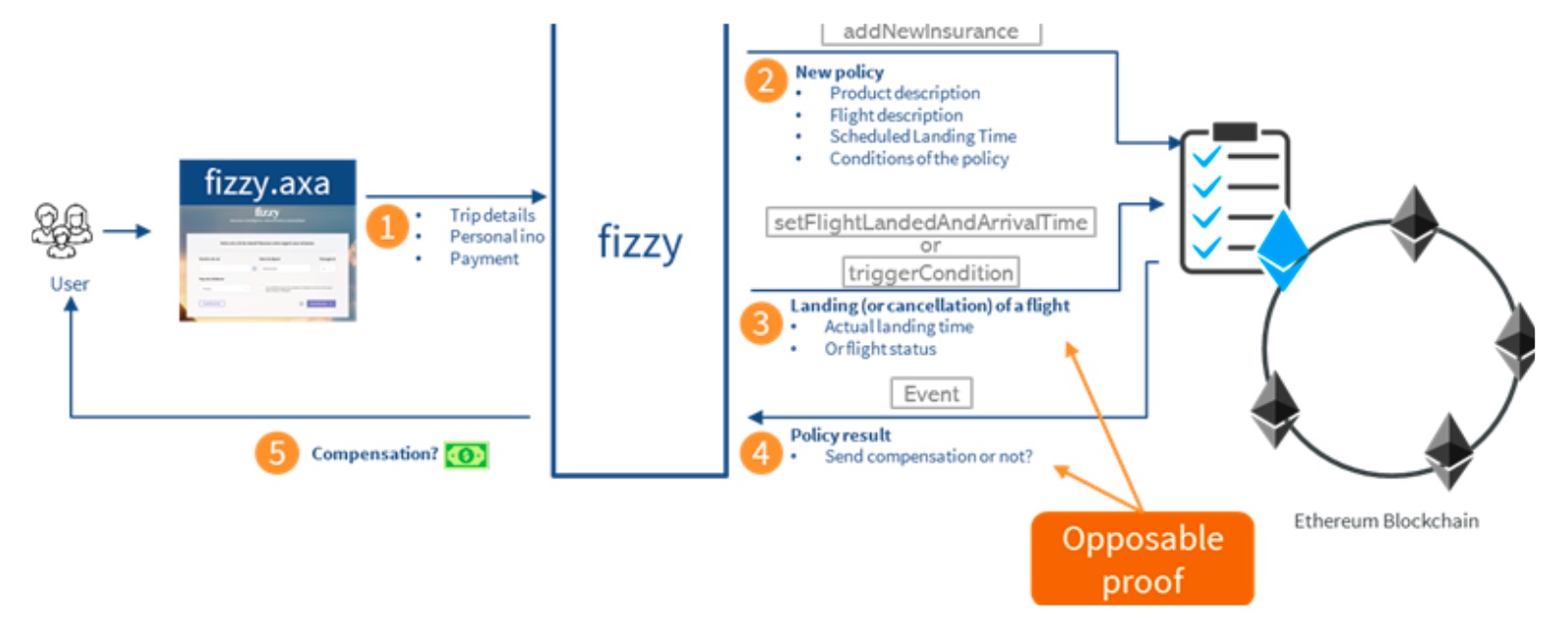

Sometimes these technologies do change everything. But sometimes they don't. And in the process of the hype cycle, they consume all the oxygen in the room. Sadly, they often bring down genuinely good ideas with them as in the case of AXA's auto payout flight insurance product, Fizzy, launched in 2017.

I genuinely believed that Fizzy was a great idea. It was a simple, easy to understand insurance product that paid out automatically if your flight was delayed.

Only 13% of consumers trust their insurer and auto payouts based on flight data seemed like a great way to build trust. However, the initiative was so bound up in the hot new technology of blockchain that when the hype cycle ended, the product was quietly retired.

External technologies turn from a joke to revolution overnight

When I think of the metaverse my mind immediately returns to 2013-14, when I used to lug an Oculus Rift (plus gaming laptop) to various offices around the UK. I'd then transport people to an often vertigo inducing world of rollercoasters and Tuscan villas.

So when Mark Zuckerburg announced Facebook's push into the metaverse in October 2021, it gave me a warm feeling of nostalgia. Sadly, though, the dream didn't quite live up to the reality and The Guardian pronounced the metaverse dead in May 2023.

But in September something strange happened. Meta's metaverse rose from the dead with a stunning new demo of its photorealistic capabilities. Lex Fridman, who sees a lot of new tech, seems genuinely amazed by this new demo - reminiscent of the famous Arthur C. Clarke quote "Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic".

Regardless of what you think of the metaverse now, it's no longer a joke. I have visions of companies like Disney who shelved their entire metaverse division earlier this year scrambling to get back into the game.

This extreme joke to revolution pivot is hard to deal with because the political and social capital required to get a project off the ground is so high. Why would you want to risk your reputation on something that could be the subject of ridicule in a few months time?

Focus on what you can control

If Epictetus was alive today he'd probably be saying something like "yeah sure, all that might be true, but happiness and freedom begin with a clear understanding of one principle: some things are within our control, and some things are not."

He sounds like an innovation consultant. It's all about the internal innovation strategy and culture you have. Control for uncertainty by building uncertainty into the model.

In 2015 I was part of a team that helped launch and embed PACE, ING's new innovation methodology into the organisation. The strategy used all the best practice of the time - lean startup, design thinking, agile, etc and led to lots of great innovations. It was the complete opposite of the lab opens/lab closes pattern I'd seen in other organisations.

One of the innovations that came out of this strategy was Yolt, a money management app. Customers genuinely loved it, they made billions of API calls and the service had 1.6 million users in the UK, France and Italy.

Yet in 2022 ING killed Yolt saying "[We] continuously evaluate activities, including assessing whether they are likely to achieve the preferred scale in their market within a reasonable time frame. In this context, the evaluation has led to the decision to phase out Yolt."

Preferred scale? The app had 1.6 million users. Lots of consumer facing apps would kill for that kind of scale. Reasonable time frame? They'd achieved this in a few years.

And yet, it raised an interesting question in my mind: people often talk about the importance of "failing" in innovation initiatives. But what about succeeding? How do you know when an innovation has worked? The PACE strategy was so focussed on failing fast it almost forgot about what to do if an innovation succeeded.

The more I think about this problem, the more I see it. I once had a conversation with a senior executive tasked with sourcing ideas from the business: "It's like I'm a fisherman for ideas, but everything in my net is absolute rubbish".

But if you're a fisherman, you really need to know what kind of fish you're looking for before you set out to sea. You don't want to accidentally catch a great white shark.

Innovation metrics often prevent any transformative innovation

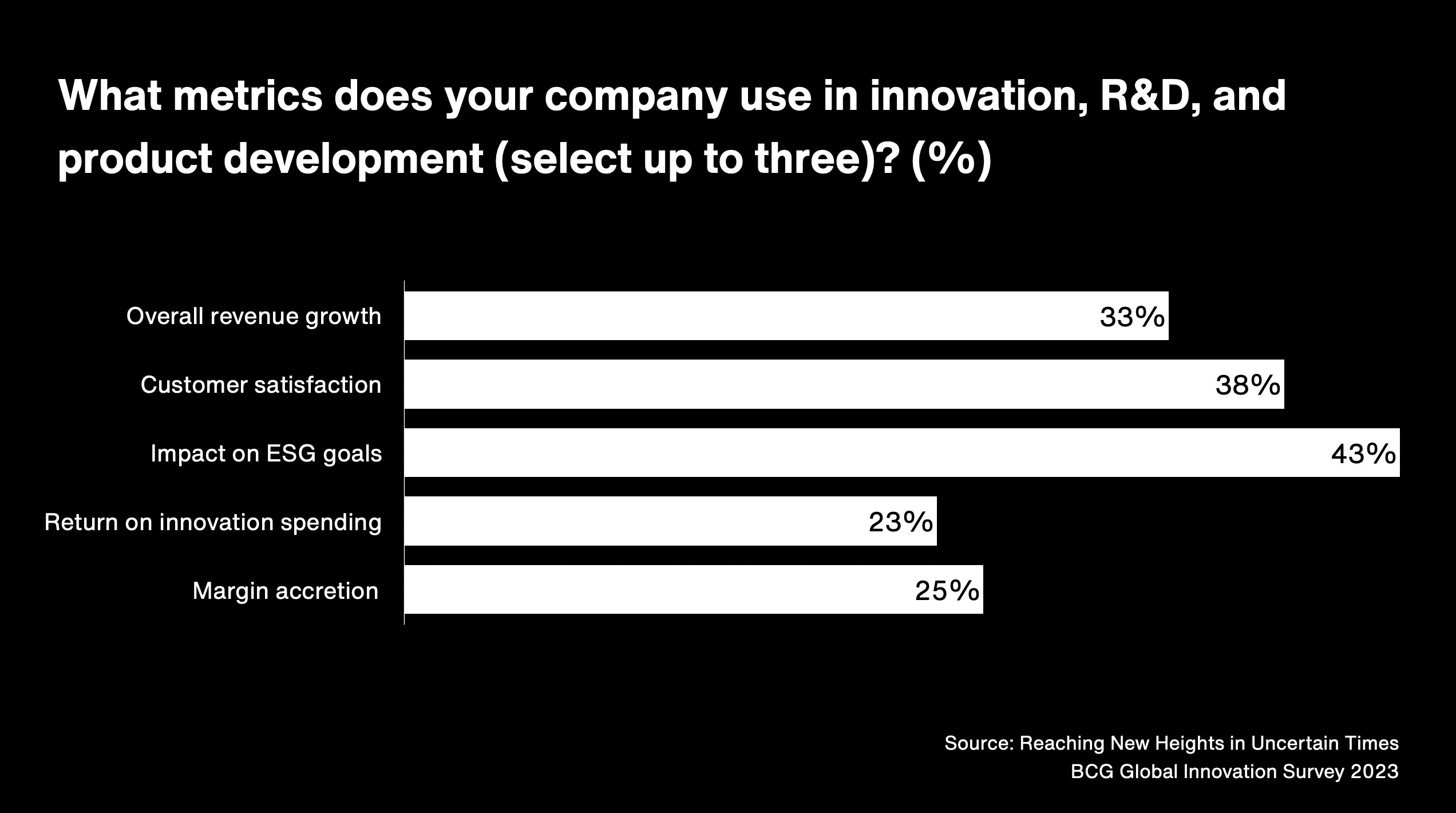

As the Yolt case demonstrates, choosing the right metrics for a change or innovation initiative is critical. So how are companies doing it? Another chart found in my innovation report digging is from a 2023 BCG Global Innovation survey.

There are several things I don't understand about this chart. For one, the percentages add up to more than 100. I think this has to do with the "select up to three" element of the question. But there's a nice medium is the message point: measuring innovation successfully is often more complex than actually doing it.

If you get the metrics wrong, you end up with some pretty significant unintended consequences. Take, for example, an innovation metric like 100% electric vehicle sales by 2035, used to galvanise car manufactures, infrastructure providers and the whole world's economic machine.

The main reason we're doing this - presumably - is to reduce carbon emissions, thus keeping this planet habitable, thus prevent human suffering.

But there's a problem. Not only are EV supply chains riddled with environmental and social issues, but car tyres produce more particle pollution than exhausts. A recent study found that tire dust makes up the majority of ocean microplastics.

To make matters worse, heavier cars that have faster acceleration and higher top speeds are more likely to produce more tire dust. So EVs are potentially worse air polluters than their ICE counterparts.

The World Health Organization estimated that ambient air pollution caused 4.2 million deaths in 2019.

This is not to say that we shouldn't be moving to EVs, but it's a good example of how a well intentioned metric can have unintended consequences.

As David Zipper, Visiting Fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School's Taubman Center puts it "None of this is inevitable. EVs don’t need to be so massive and lightning-fast—these are choices that the auto industry has made."

Organisations and individuals will always optimise to the metric - understandably - because otherwise they'll be taxed, imprisoned or fired. Examples abound. Lego ditching their sustainable brick because it actually pollutes more heavily, company executives gaming ESG metrics to boost their bonuses, or the fallacy of carbon credits.

Innovation metrics that work

Part of the reason why startups tend to innovate so well is the metric their working with is simple: survival. When the immediacy of the existential threat is slightly removed things get more difficult.

However, there are two examples that I think point to a way forward:

-

FT's RFV North Star

The FT have a well documented case study about how they moved from product-centric metrics like page views or conversion rates to more customer centric metrics.In the end they arrived at RFV - recency, frequency, volume - as their north star metric. This simple metric correlates with product-centric metrics but is fundamentally about reader engagement - a human based outcome.

-

Voodoo's CPI/D1/D7

Voodoo is a gaming company with over 6 billion downloads. They innovate relentlessly, bringing new games to market all the time.They have a simple metric that they use to measure the success of their games: CPI/D1/D7. CPI is the cost per install, D1 is the number of people who play the game on the first day, and D7 is the number of people who play the game on the seventh day.

In a similar way to the FT, this measure is fundamentally about a human based outcome: how many people are enjoying the game we've made, and how much did it cost to get them to play it?

Having clearly defined innovation metrics with human-based outcomes allows everyone in the organisation to optimise around an end, rather than a means. It also allows you to measure the success of an innovation initiative in a way that's not tied to the technology or the hype cycle.

Conclusion

As the world becomes more complex and moves faster, innovation in large organisations is becoming harder than ever. Yet to survive and thrive, change is desperately needed.

A good starting point is to review the innovation metrics you're using. Are they human based? Are they tied to the technology or the hype cycle? Are they simple enough to be understood by everyone in the organisation?

For example:

| Non-human based outcome | Human based outcome |

| Increase article traffic | Increase % of readers engaged |

| Increase number of downloads | Increase % of players enjoying the game |

| Increase number of EVs | % of people who breathe clean air |

Finally, if you don't trust me, trust Arnold Schwarzenegger. In a May 2023 interview he said:

As long as they keep talking about global climate change, they are not gonna go anywhere. ‘Cause no one gives a s--- about that. So my thing is, let’s go and rephrase this and communicate differently about it and really tell people — we’re talking about pollution. Pollution creates climate change, and pollution kills [people]

The full interview is definitely worth a watch.