TL;DR - A simple mission to write a guide for some people on Reddit on how to create a plane spotting screen led me down a deep ADS-B rabbit hole and ended with me building a clock.

Read on for a guide to build a screen yourself (GitHub repo here), or if you can't be bothered to source the components and run your own ADS-B station, I can send you a kit with everything you need to set up a clock like the one above.

The idea

I've lived in West London my whole life, mostly under the main flight path to London Heathrow. Hour after hour, day after day, planes queue up to land. Around 240,000 of them each year.

As well as being loud and polluting, there's something undeniably inspiring about a tin can hurtling through the air with hundreds of people inside. Planes are a visible emblem of the awesome achievement of the human race (and of our ultimate destruction too).

A question I've often wondered when looking up is: where in the world has that piece of metal and plastic come from? Knowing that a plane is American Airlines flight AAL134 from Los Angeles or EgyptAir MS777 from Cairo changes an anonymous speck in the sky into countless imagined stories of couples returning from honeymoon, businesspeople prepping for meetings or students coming to start the new academic year.

Yes, I can (and often do) open FlightRadar24 to find out where the plane above me has come from - but monitoring the origin of an arriving aircraft every 20 seconds is slightly disruptive to getting anything in life done. (And that's without mentioning the circling helicopters).

Sitting at my desk watching the relentless queue of planes one day, I thought to myself: what if a small screen could quietly announce the origin of each flight? Surely it can't be that difficult to build such a thing?

Building the screen

The first problem to solve is figuring out if a plane is actually flying overhead. I could have just used an unofficial FlightRadar24 API, but the issues with these wrappers are that they are are against the FlightRadar24 terms of service and may stop working at any time. As well as this, FlightRadar24 filters out sensitive military traffic and some private jets, so you won't get the full picture of what's flying overhead.

Luckily, under International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) regulations, all commercial aircraft must be equipped with an ADS-B (Automatic Dependent Surveillance–Broadcast) system. This broadcasts an aircraft's position (and some other data) up to several times a second. This signal is decodable by anyone with the right kind of aerial - and you can buy an aerial for next to nothing.

Processing raw ADS-B isn't much fun (though probably more fun than processing raw AIS data), because it looks like this:

MSG,1,111,11111,A12345,11111,2024/10/01,12:30:15.000,2024/10/01,12:30:14.000,DLH1234,,,,,,,,,,,

MSG,3,111,11111,A12345,11111,2024/10/01,12:30:15.000,2024/10/01,12:30:14.000,,38000,,,-33.000123,150.000456,,,,,,

MSG,4,111,11111,A12345,11111,2024/10/01,12:30:15.000,2024/10/01,12:30:14.000,,,450.0,90.0,,,-64,,,,,,

Luckily you can buy a USB stick that not only collects the raw ADS-B signals of planes (and helis) in range, but processes them and provides a map and an easy to read JSON endpoint. There are a few USB sticks available, but the FlightAware Pro Stick Plus is great and only costs around £50/$40. You'll also need an antenna (I got this one for £5).

Next, we need a device to process and store the data - I used the Raspberry Pi 5. Setting up the FlightAware stick with a Raspberry Pi is really easy - instructions are here.

Initial prototype

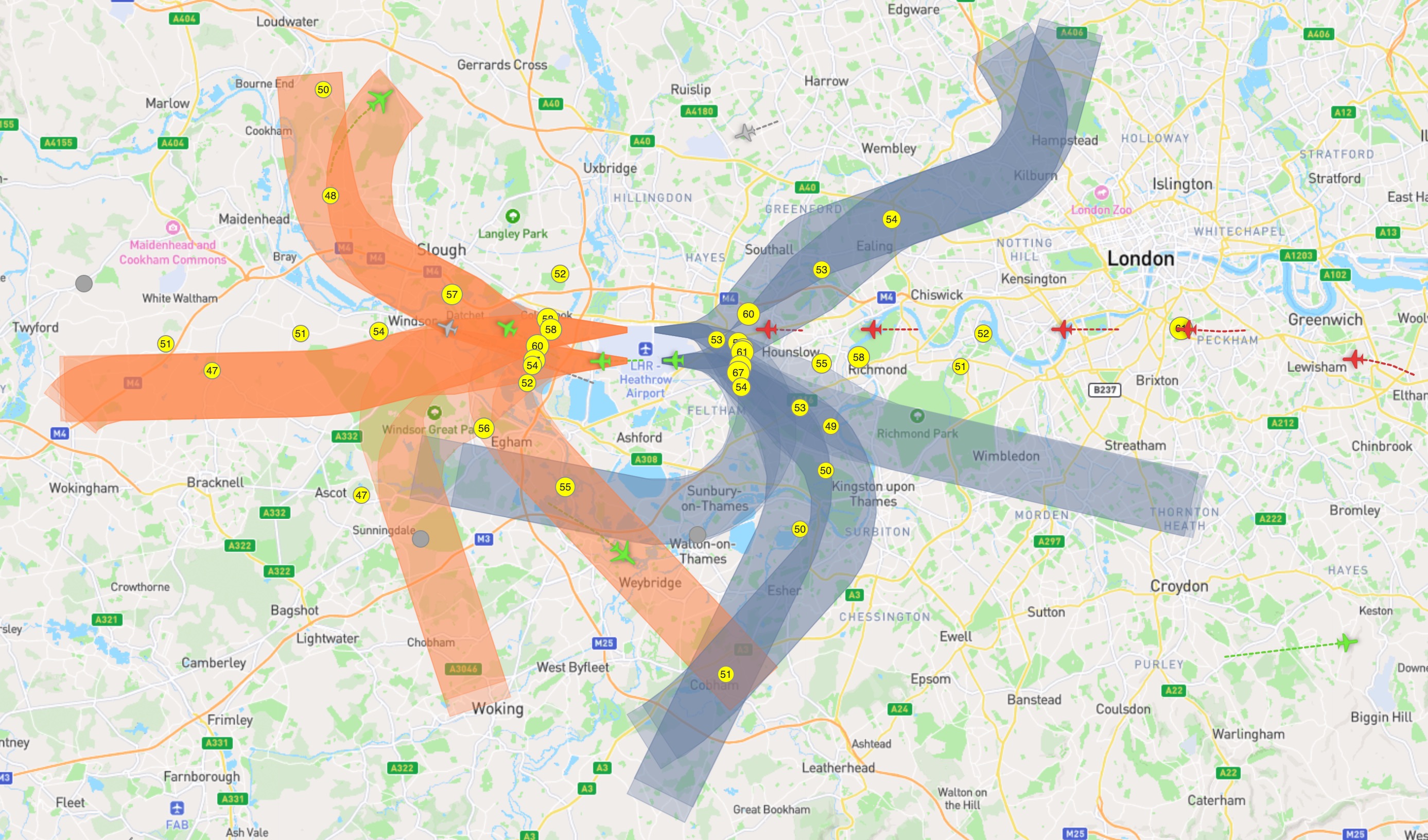

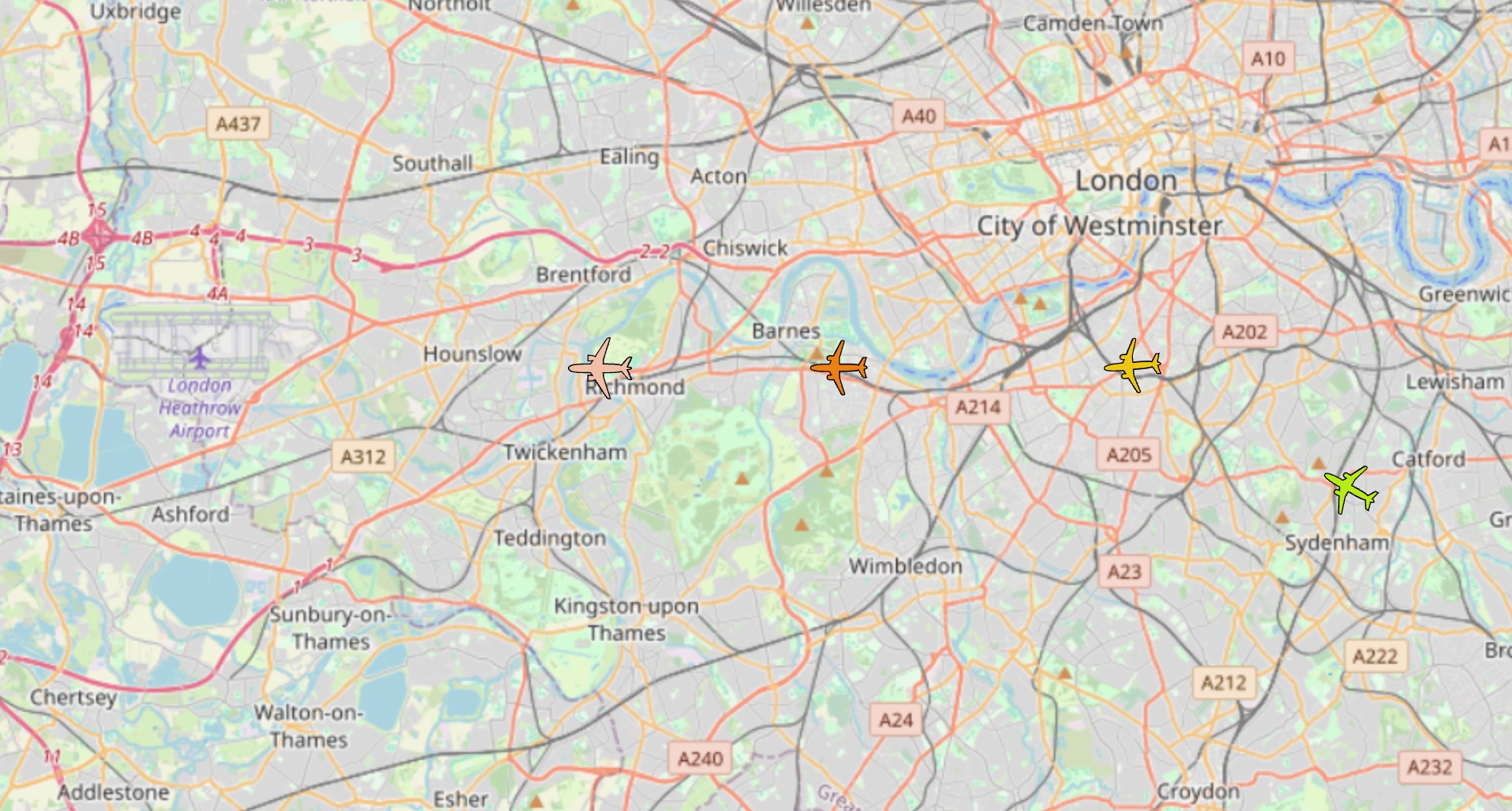

Now we've got a map of live planes in our local area - cool!

To display the data we need to process the latitudes and longitudes of all the aircraft, selecting just the ones that are directly overhead. FlightAware provides a local JSON endpoint at /data/aircraft.json which looks much more sensible than the raw ADS-B:

aircraft: [

{

hex: "405a49",

flight: "BAW777C ",

alt_baro: 4600,

alt_geom: 4600,

emergency: "none",

category: "A3",

nav_heading: 244.7,

lat: 51.475342,

lon: -0.077424,

},

...

]

Using the Haversine forumula we can calculate the exact distance between our location and all the aircraft picked up by the ADS-B antenna. When a plane comes within, say, 2KM, we can display it.

The call sign nightmare begins

ADS-B is a brilliant format for air traffic control. It provides a unique ICAO identifier ( 405a49 in the JSON example above), a call sign (BAW777C in the JSON example above), speed, heading and location. But this isn't massively useful for our purposes. Nothing about the routing or flight number is provided as part of the ADS-B message.

The value labeled "flight" in the JSON above is also frustratingly deceptive. BAW777C looks like a flight number, but it's not, it's the call sign. The flight number of this aircraft is BA777. It's similar, but just different enough to mess everything up.

An explanation of why this (regrettably) makes sense is detailed in this FlightRadar24 blog. Essentially: flight numbers can sound very similar to each other so the industry moved to alphanumeric call signs (adding letters on to the flight number).

However, decoding the flight number - and thus the route - isn't as simple as removing the last letter of a call sign. Some airlines seem to enjoy not synchronising the call sign and flight number at all.

| Call Sign | Flight Number | Airline | Does it make sense? |

|---|---|---|---|

| QTR003 | QR3 | Qatar Airways | Yes |

| TAP52LH | TP1352 | TAP Air Portugal | Sort of |

| BAW900A | BA455 | British Airways | Sort of |

| SHT19M | BA1307 | British Airways | Absolutely not* |

* For some deeply confusing reason BA domestic flights use SHT (from "shuttle" as the first letters of their call sign). And BA domestic flights operating out of London City use a CFE call sign. Because, why not?

So, whilst we could display an aircraft's call sign on our screen, SHT19M just doesn't hit right.

We need help.

Enter Mr Jack Wills & Josh Douch

One of the beautiful things about the internet is that people you've never met sometimes help you for reasons you'll never truly understand. Why Mr Jack Wills and Josh Douch have put together APIs that allow call sign to flight number/routing lookups I'll never understand. But thankfully they have.

Josh's hexdb.io and Jack's adsbdb.com ingest thousands of flight records from diverse sources and provide the data via a simple API. Most the data comes from PlaneBase - a members only database where you have to be "sponsored" by an existing user to gain access. It's a bizarre world of data trading and enthusiast forums.

Regardless of where the data comes from, these services allow us to do a single lookup to return routing information, taking a call sign like BAW900A and turning it into:

flightroute: {

callsign: "BAW900A",

callsign_icao: "BAW900A",

callsign_iata: "BA900A",

airline: {

name: "British Airways",

icao: "BAW",

iata: "BA",

country: "United Kingdom",

country_iso: "GB",

callsign: "SPEEDBIRD"

},

origin: {

country_iso_name: "ES",

country_name: "Spain",

elevation: 53,

iata_code: "AGP",

icao_code: "LEMG",

latitude: 36.6749,

longitude: -4.49911,

municipality: "Málaga",

name: "Málaga-Costa del Sol Airport"

},

destination: {

country_iso_name: "GB",

country_name: "United Kingdom",

elevation: 83,

iata_code: "LHR",

icao_code: "EGLL",

latitude: 51.4706,

longitude: -0.461941,

municipality: "London",

name: "London Heathrow Airport"

}

}

Finally, we have the origin of the flight and can display it on our screen using a simple Next.js web app. There are loads of screens you could use to display this data. I used the WaveShare 7.9in HDMI LCD initially, but it would also work on a standard monitor.

I should say at this point, all the code and instructions you need to set up a screen using your own ADS-B data and the APIs are available in this GitHub repo. And if you don't want your heart broken about data accuracy, then stop reading here.

The problem

I was pretty proud of myself for getting this far, and posted on Reddit. Unfortunately, in doing so, I revealed the severe limitations of the setup. As BourtosBourtosJolly, who recreated my original setup commented:

hexdb.io is not a great source for route information. For at least half the flights the route information is not found and for many of the cases where the route information is returned, it's inaccurate. The API call to hexdb.io returns the "updatetime" of the route information and in one case I was debugging the route was last updated in 2018.

Boutros is dead right. Both hexdb and adsbdb simply aren't accurate. Remember that ridiculous SHT19M callsign from earlier? A request to https://api.adsbdb.com/v0/callsign/SHT19M returns an "unknown callsign" response.

hexdb.io does return the correct flight number, but when tested with a slightly obscure Lufthansa Cargo flight that just went overhead, with callsign GEC8223 it cites the route as:

{

flight: "GEC8223",

route: "MMMX-KDFW-EDDF",

updatetime: 1344126159

}

This is frustratingly close. When checked on FlightRadar24, the route is actually MMMY-EDDF - in other words from Monterrey to Frankfurt direct instead of Mexico City to Frankfurt via Dallas. The last update time is also August 4th 2012, which is a slight indication that the data might not be the most up to date.

It's not Jack or Josh's fault. I often wonder if even the airlines/airports themselves actually know the correct callsign/flight number/routing pairings as the data is such a mess.

The rethink

Does any of this matter? Unfortunatley it does. The minute you start to doubt the accuracy of the data, the whole thing starts to feel a bit pointless.

In the process of experimenting and researching this guide I discovered a whole host of incredible free and open resources. And for when the open source data isn't enough, there are commercial services like FlightRadar24 that provide APIs for a small fee, though it's not feasible to look up every call sign commercially because it quickly becomes very very expensive.

A new idea emerged: what if I could combine all these sources to get the most accurate data possible? It would also mean that the form factor of the screen could be much smaller and more compact, as I wouldn't need the ADS-B stick and antenna.

If I'm honest the screen was also a bit of a monstrosity.

JetClock

My great grandfather was a clockmaker, and legend has it that he migrated from Germany to Scotland carrying just his prized grandfather clock on his back. I've always been obsessed with clocks, and now, finally, was the chance to build one. I found a 3D designer, sourced the components and iterated on the design until I had something that I could look at all day.

Initially I tried living with a window mounted version:

But I eventually settled on the familiar desk clock form factor. I also experimented with some different materials and finishes and didn't realise how expensive 3D printing was until I started using PA12 Nylon with a satin black finish.

A couple of other upgrades

While I was fixing the fundamental issues, I managed to integrate npeezy's extremely brilliant suggestion of having an arrow that tracks towards the aircraft location as it moves. I also experimented with a few different clock faces, including moon phases and a weather display. The weather ones ended up being my favourite, and when the planes are on easterly operations, the clock face looks like this:

I've been surprised at how useful having a desk clock connected to the internet has been (especially from a home automation point of view).

I'm currently working on visualing my home's live energy use, internal temperate and humidity as well as meetings and calendar events. So what started as a simple plane spotting screen has turned into a fully fledged home dashboard.

Build a screen yourself

All the code and instructions you need to set up a screen using your own ADS-B data and the adsbdb API are available on GitHub.

Get the kit

I can send you a kit with everything you need for the clock version, using the API that I built. You can assemble it in minutes and need no technical knowledge. If you're interested in a kit, you can find it here.